Spherical harmonics

In mathematics, the spherical harmonics are the angular portion of a set of solutions to Laplace's equation. Represented in a system of spherical coordinates, Laplace's spherical harmonics  are a specific set of spherical harmonics that forms an orthogonal system, first introduced by Pierre Simon de Laplace.[1] Spherical harmonics are important in many theoretical and practical applications, particularly in the computation of atomic orbital electron configurations, representation of gravitational fields, geoids, and the magnetic fields of planetary bodies and stars, and characterization of the cosmic microwave background radiation. In 3D computer graphics, spherical harmonics play a special role in a wide variety of topics including indirect lighting (ambient occlusion, global illumination, precomputed radiance transfer, etc.) and in recognition of 3D shapes.

are a specific set of spherical harmonics that forms an orthogonal system, first introduced by Pierre Simon de Laplace.[1] Spherical harmonics are important in many theoretical and practical applications, particularly in the computation of atomic orbital electron configurations, representation of gravitational fields, geoids, and the magnetic fields of planetary bodies and stars, and characterization of the cosmic microwave background radiation. In 3D computer graphics, spherical harmonics play a special role in a wide variety of topics including indirect lighting (ambient occlusion, global illumination, precomputed radiance transfer, etc.) and in recognition of 3D shapes.

History

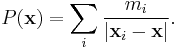

Spherical harmonics were first investigated in connection with the Newtonian potential of Newton's law of universal gravitation in three dimensions. In 1782, Pierre-Simon de Laplace had, in his Mécanique Céleste, determined that the gravitational potential associated to a set of point masses mi located at points xi was given by

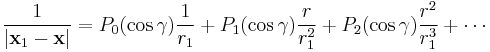

Each term in the above summation is an individual Newtonian potential for a point mass. Just prior to that time, Adrien-Marie Legendre had investigated the expansion of the Newtonian potential in powers of r = |x| and r1 = |x1|. He discovered that

where γ is the angle between the vectors x and x1. The coefficients Pi are the Legendre polynomials, and they are a special case of spherical harmonics. Subsequently, in his 1782 memoire, Laplace investigated these coefficients using spherical coordinates to represent the angle γ between x1 and x. (See Applications of Legendre polynomials in physics for a more detailed analysis.)

In 1867, William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and Peter Guthrie Tait introduced the solid spherical harmonics in their Treatise on Natural Philosophy, and also first introduced the name of "spherical harmonics" for these functions. The solid harmonics were homogeneous solutions of Laplace's equation

By examining Laplace's equation in spherical coordinates, Thomson and Tait recovered Laplace's spherical harmonics. The term "Laplace's coefficients" was employed by William Whewell to describe the particular system of solutions introduced along these lines, whereas others reserved this designation for the zonal spherical harmonics that had properly been introduced by Laplace and Legendre.

The 19th century development of Fourier series made possible the solution of a wide variety of physical problems in rectangular domains, such as the solution of the heat equation and wave equation. This could be achieved by expansion of functions in series of trigonometric functions. Whereas the trigonometric functions in a Fourier series represent the fundamental modes of vibration in a string, the spherical harmonics represent the fundamental modes of vibration of a sphere in much the same way. Many aspects of the theory of Fourier series could be generalized by taking expansions in spherical harmonics rather than trigonometric functions. This was a boon for problems possessing spherical symmetry, such as those of celestial mechanics originally studied by Laplace and Legendre.

The prevalence of spherical harmonics already in physics set the stage for their later importance in the 20th century birth of quantum mechanics. The spherical harmonics are eigenfunctions of the square of the orbital angular momentum operator

and therefore they represent the different quantized configurations of atomic orbitals.

Laplace's spherical harmonics

for

for  to

to  (top to bottom) and

(top to bottom) and  to

to  (left to right). The negative order harmonics

(left to right). The negative order harmonics  are rotated about the

are rotated about the  axis by

axis by  with respect to the positive order ones.

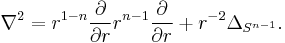

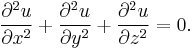

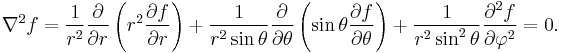

with respect to the positive order ones.Laplace's equation imposes that the divergence of the gradient of a scalar field f is zero. In spherical coordinates this is:[2]

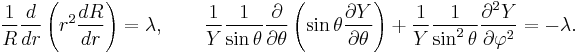

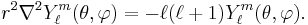

Consider the problem of finding solutions of the form ƒ(r,θ,φ) = R(r)Y(θ,φ). By separation of variables, two differential equations result by imposing Laplace's equation:

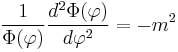

The second equation can be simplified under the assumption that Y has the form Y(θ,φ) = Θ(θ)Φ(φ). Applying separation of variables again to the second equation gives way to the pair of differential equations

for some number m. A priori, m is a complex constant, but because Φ must be a periodic function whose period evenly divides 2π, m is necessarily an integer and Φ is a linear combination of the complex exponentials e±imφ. The solution function Y(θ,φ) is regular at the poles of the sphere, where θ=0,π. Imposing this regularity in the solution Θ of the second equation at the boundary points of the domain is a Sturm–Liouville problem that forces the parameter λ to be of the form λ = ℓ(ℓ+1) for some non-negative integer with ℓ ≥ |m|; this is also explained below in terms of the orbital angular momentum. Furthermore, a change of variables t = cosθ transforms this equation into the Legendre equation, whose solution is a multiple of the associated Legendre polynomial  . Finally, the equation for R has solutions of the form R(r) = Arℓ + Br−ℓ−1; requiring the solution to be regular throughout R3 forces B = 0.[3]

. Finally, the equation for R has solutions of the form R(r) = Arℓ + Br−ℓ−1; requiring the solution to be regular throughout R3 forces B = 0.[3]

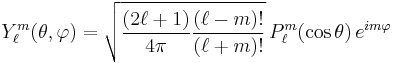

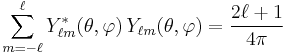

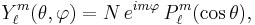

Here the solution was assumed to have the special form Y(θ,φ) = Θ(θ)Φ(φ). For a given value of ℓ, there are 2ℓ+1 independent solutions of this form, one for each integer m with −ℓ ≤ m ≤ ℓ. These angular solutions are a product of trigonometric functions, here represented as a complex exponential, and associated Legendre polynomials:

which fulfill

Here  is called a spherical harmonic function of degree ℓ and order m,

is called a spherical harmonic function of degree ℓ and order m,  is an associated Legendre polynomial, N is a normalization constant, and θ and φ represent colatitude and longitude, respectively. In particular, the colatitude θ, or polar angle, ranges from 0 at the North Pole to π at the South Pole, assuming the value of π/2 at the Equator, and the longitude φ, or azimuth, may assume all values with 0 ≤ φ < 2π. For a fixed integer ℓ, every solution Y(θ,φ) of the eigenvalue problem

is an associated Legendre polynomial, N is a normalization constant, and θ and φ represent colatitude and longitude, respectively. In particular, the colatitude θ, or polar angle, ranges from 0 at the North Pole to π at the South Pole, assuming the value of π/2 at the Equator, and the longitude φ, or azimuth, may assume all values with 0 ≤ φ < 2π. For a fixed integer ℓ, every solution Y(θ,φ) of the eigenvalue problem

is a linear combination of  . In fact, for any such solution, rℓY(θ,φ) is the expression in spherical coordinates of a homogeneous polynomial that is harmonic (see below), and so counting dimensions shows that there are 2ℓ+1 linearly independent such polynomials.

. In fact, for any such solution, rℓY(θ,φ) is the expression in spherical coordinates of a homogeneous polynomial that is harmonic (see below), and so counting dimensions shows that there are 2ℓ+1 linearly independent such polynomials.

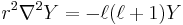

The general solution to Laplace's equation in a ball centered at the origin is a linear combination of the spherical harmonic functions multiplied by the appropriate scale factor rℓ,

where the  are constants and the factors

are constants and the factors  are known as solid harmonics. Such an expansion is valid in the ball

are known as solid harmonics. Such an expansion is valid in the ball

Orbital angular momentum

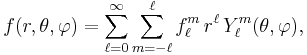

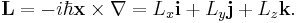

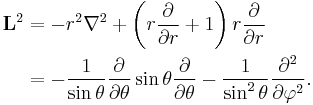

In quantum mechanics, Laplace's spherical harmonics are understood in terms of the orbital angular momentum[4]

The  is conventional in quantum mechanics; it is convenient to work in units in which

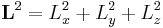

is conventional in quantum mechanics; it is convenient to work in units in which  . The spherical harmonics are eigenfunctions of the square of the orbital angular momentum

. The spherical harmonics are eigenfunctions of the square of the orbital angular momentum

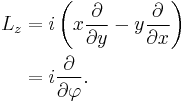

Laplace's spherical harmonics are the joint eigenfunctions of the square of the orbital angular momentum and the generator of rotations about the azimuthal axis:

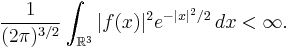

These operators commute, and are densely defined self-adjoint operators on the Hilbert space of functions ƒ square-integrable with respect to the normal distribution on R3:

Furthermore, L2 is a positive operator.

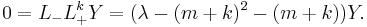

If Y is a joint eigenfunction of L2 and Lz, then by definition

for some real numbers m and λ. Here m must in fact be an integer, for Y must be periodic in the coordinate φ with period a number that evenly divides 2π. Furthermore, since

and each of Lx, Ly, Lz are self-adjoint, it follows that λ ≥ m2.

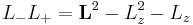

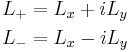

Denote this joint eigenspace by Eλ,m, and define the raising and lowering operators by

Then L+ and L− commute with L2, and the Lie algebra generated by L+, L−, Lz is the special linear Lie algebra, with commutation relations

Thus L+ : Eλ,m → Eλ,m+1 (it is a "raising operator") and L− : Eλ,m → Eλ,m−1 (it is a "lowering operator"). In particular, Lk+ : Eλ,m → Eλ,m+k must be zero for k sufficiently large, because the inequality λ ≥ m2 must hold in each of the nontrivial joint eigenspaces. Let Y ∈ Eλ,m be a nonzero joint eigenfunction, and let k be the least integer such that

Then, since

it follows that

Thus λ = ℓ(ℓ+1) for the positive integer ℓ = m+k.

Conventions

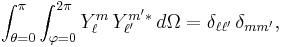

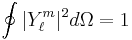

Orthogonality and normalization

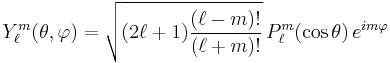

Several different normalizations are in common use for the Laplace spherical harmonic functions. In physics and seismology, these functions are generally defined as

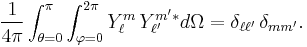

which are orthonormal

where δaa = 1, δab = 0 if a ≠ b, (see Kronecker delta) and dΩ = sinθ dφ dθ. This normalization is used in quantum mechanics because it ensures that probability is normalized, ie.  . The disciplines of geodesy and spectral analysis use

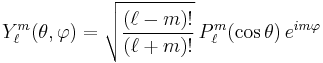

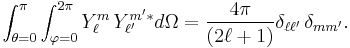

. The disciplines of geodesy and spectral analysis use

which possess unit power

The magnetics community, in contrast, uses Schmidt semi-normalized harmonics

which have the normalization

In quantum mechanics this normalization is often used as well, and is named Racah's normalization after Giulio Racah.

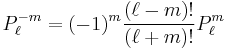

Using the identity (see associated Legendre polynomials)

it can be shown that all of the above normalized spherical harmonic functions satisfy

where the superscript * denotes complex conjugation. Alternatively, this equation follows from the relation of the spherical harmonic functions with the Wigner D-matrix.

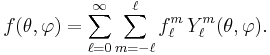

Condon–Shortley phase

One source of confusion with the definition of the spherical harmonic functions concerns a phase factor of (−1) m, commonly referred to as the Condon–Shortley phase in the quantum mechanical literature. In the quantum mechanics community, it is common practice to either include this phase factor in the definition of the associated Legendre polynomials, or to append it to the definition of the spherical harmonic functions. There is no requirement to use the Condon–Shortley phase in the definition of the spherical harmonic functions, but including it can simplify some quantum mechanical operations, especially the application of raising and lowering operators. The geodesy and magnetics communities never include the Condon–Shortley phase factor in their definitions of the spherical harmonic functions.

Real form

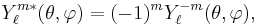

A real basis of spherical harmonics is given by setting instead

where  denotes the normalization constant as a function of ℓ and

denotes the normalization constant as a function of ℓ and  . The real form requires only associated Legendre polynomials

. The real form requires only associated Legendre polynomials  of non-negative |m|. The harmonics with m > 0 are said to be of cosine type, and those with m < 0 of sine type. These real spherical harmonics are sometimes known as tesseral spherical harmonics.[5] These functions have the same normalization properties as the complex ones above. See here for a list of real spherical harmonics up to and including

of non-negative |m|. The harmonics with m > 0 are said to be of cosine type, and those with m < 0 of sine type. These real spherical harmonics are sometimes known as tesseral spherical harmonics.[5] These functions have the same normalization properties as the complex ones above. See here for a list of real spherical harmonics up to and including  . Note, however, that the listed functions differ by the phase (−1) m from the phase given in this article.

. Note, however, that the listed functions differ by the phase (−1) m from the phase given in this article.

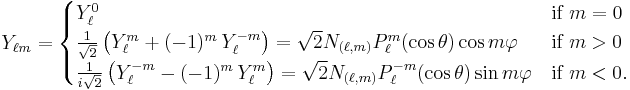

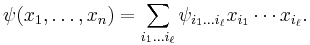

Spherical harmonics expansion

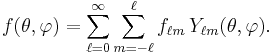

The Laplace spherical harmonics form a complete set of orthonormal functions and thus form an orthonormal basis of the Hilbert space of square-integrable functions. On the unit sphere, any square-integrable function can thus be expanded as a linear combination of these:

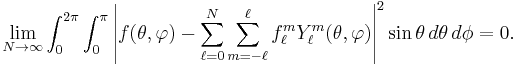

This expansion holds in the sense of mean-square convergence — convergence in L2 of the sphere — which is to say that

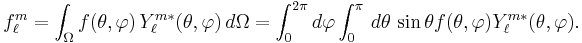

The expansion coefficients are the analogs of Fourier coefficients, and can be obtained by multiplying the above equation by the complex conjugate of a spherical harmonic, integrating over the solid angle  , and utilizing the above orthogonality relationships. This is justified rigorously by basic Hilbert space theory. For the case of orthonormalized harmonics, this gives:

, and utilizing the above orthogonality relationships. This is justified rigorously by basic Hilbert space theory. For the case of orthonormalized harmonics, this gives:

If the coefficients decay in ℓ sufficiently rapidly — for instance, exponentially — then the series also converges uniformly to ƒ.

A real square-integrable function ƒ can be expanded in terms of the real harmonics Yℓm above as a sum

Convergence of the series holds again in the same sense.

Spectrum analysis

Power spectrum in signal processing

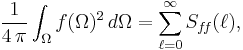

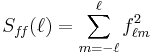

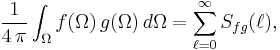

The total power of a function ƒ is defined in the signal processing literature as the integral of the function squared, divided by the area of its domain. Using the orthonormality properties of the real unit-power spherical harmonic functions, it is straightforward to verify that the total power of a function defined on the unit sphere is related to its spectral coefficients by a generalization of Parseval's theorem:

where

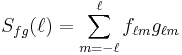

is defined as the angular power spectrum. In a similar manner, one can define the cross-power of two functions as

where

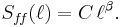

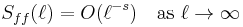

is defined as the cross-power spectrum. If the functions ƒ and g have a zero mean (i.e., the spectral coefficients ƒ00 and g00 are zero), then Sƒƒ(ℓ) and Sƒg(ℓ) represent the contributions to the function's variance and covariance for degree ℓ, respectively. It is common that the (cross-)power spectrum is well approximated by a power law of the form

When β = 0, the spectrum is "white" as each degree possesses equal power. When β < 0, the spectrum is termed "red" as there is more power at the low degrees with long wavelengths than higher degrees. Finally, when β > 0, the spectrum is termed "blue". The condition on the order of growth of Sƒƒ(ℓ) is related to the order of differentiability of ƒ in the next section.

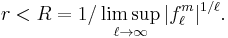

Differentiability properties

One can also understand the differentiability properties of the original function ƒ in terms of the asymptotics of Sƒƒ(ℓ). In particular, if Sƒƒ(ℓ) decays faster than any rational function of ℓ as ℓ → ∞, then ƒ is infinitely differentiable. If, furthermore, Sƒƒ(ℓ) decays exponentially, then ƒ is actually real analytic on the sphere.

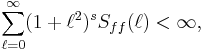

The general technique is to use the theory of Sobolev spaces. Statements relating the growth of the Sƒƒ(ℓ) to differentiability are then similar to analogous results on the growth of the coefficients of Fourier series. Specifically, if

then ƒ is in the Sobolev space Hs(S2). In particular, the Sobolev embedding theorem implies that ƒ is infinitely differentiable provided that

for all s.

Algebraic properties

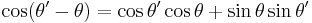

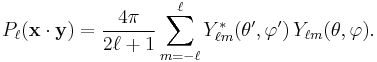

- Addition theorem

A mathematical result of considerable interest and use is called the addition theorem for spherical harmonics. This is a generalization of the trigonometric identity

in which the role of the trigonometric functions appearing on the right-hand side is played by the spherical harmonics and that of the left-hand side is played by the Legendre polynomials.

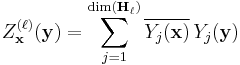

Consider two unit vectors x and y, having spherical coordinates (θ,φ) and (θ′,φ′), respectively. The addition theorem states

-

(

where Pℓ is the Legendre polynomial of degree ℓ. This expression is valid for both real and complex harmonics.[6] The result can be proven analytically, using the properties of the Poisson kernel in the unit ball, or geometrically by applying a rotation to the vector y so that it points along the z-axis, and then directly calculating the right-hand side.[7]

In particular, when x = y, this gives Unsöld's theorem[8]

which generalizes the identity cos2θ + sin2θ = 1 to two dimensions.

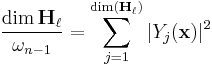

In the expansion (1), the left-hand side Pℓ(x·y) is a constant multiple of the degree ℓ zonal spherical harmonic. From this perspective, one has the following generalization to higher dimensions. Let Yj be an arbitrary orthonormal basis of the space Hℓ of degree ℓ spherical harmonics on the n-sphere. Then  , the degree ℓ zonal harmonic corresponding to the unit vector x, decomposes as[9]

, the degree ℓ zonal harmonic corresponding to the unit vector x, decomposes as[9]

-

(

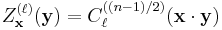

Furthermore, the zonal harmonic  is given as a constant multiple of the appropriate Gegenbauer polynomial:

is given as a constant multiple of the appropriate Gegenbauer polynomial:

-

(

Combining (2) and (3) gives (1) in dimension n = 2 when x and y are represented in spherical coordinates. Finally, evaluating at x = y gives the functional identity

where ωn−1 is the volume of the (n−1)-sphere.

- Clebsch-Gordan coefficients

The Clebsch-Gordan coefficients are the coefficients appearing in the expansion of the product of two spherical harmonics in terms of spherical harmonics itself. A variety of techniques are available for doing essentially the same calculation, including the Wigner 3-jm symbol, the Racah coefficients, and the Slater integrals. Abstractly, the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients express the tensor product of two irreducible representations of the rotation group as a sum of irreducible representations: suitably normalized, the coefficients are then the multiplicities.

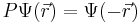

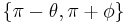

- Parity

The spherical harmonics have well defined parity in the sense that they are either even or odd with respect to reflection about the origin. Reflection about the origin is represented by the operator  . For the spherical angles,

. For the spherical angles,  this corresponds to the replacement

this corresponds to the replacement  . The associated Legendre polynomials gives (−1)ℓ-m and from the exponential function we have (−1)m, giving together for the spherical harmonics a parity of (-1)ℓ:

. The associated Legendre polynomials gives (−1)ℓ-m and from the exponential function we have (−1)m, giving together for the spherical harmonics a parity of (-1)ℓ:

This remains true for spherical harmonics in higher dimensions: applying a point reflection to a spherical harmonic of degree ℓ changes the sign by a factor of (−1)ℓ.

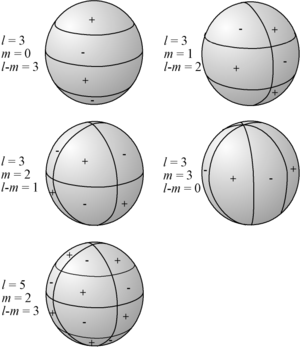

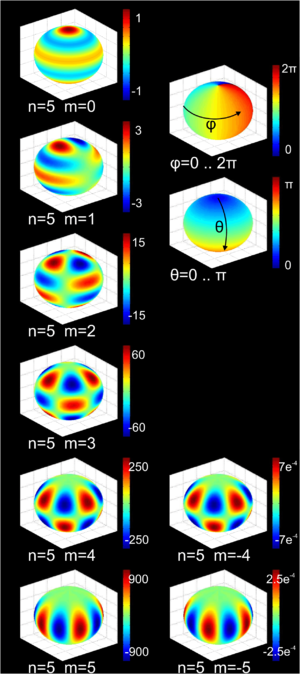

Visualization of the spherical harmonics

on the unit sphere and its nodal lines.

on the unit sphere and its nodal lines.  is equal to 0 along

is equal to 0 along  great circles passing through the poles, and along

great circles passing through the poles, and along  circles of equal latitude. The function changes sign each time it crosses one of these lines.

circles of equal latitude. The function changes sign each time it crosses one of these lines.

The Laplace spherical harmonics  can be visualized by considering their "nodal lines", that is, the set of points on the sphere where

can be visualized by considering their "nodal lines", that is, the set of points on the sphere where  vanishes. Nodal lines of

vanishes. Nodal lines of  are composed of circles: some are latitudes and others are longitudes. One can determine the number of nodal lines of each type by counting the number of zeros of

are composed of circles: some are latitudes and others are longitudes. One can determine the number of nodal lines of each type by counting the number of zeros of  in the latitudinal and longitudinal directions independently. For the latitudinal direction, the associated Legendre polynomials possess ℓ−|m| zeros, whereas for the longitudinal direction, the trigonometric sin and cos functions possess 2|m| zeros.

in the latitudinal and longitudinal directions independently. For the latitudinal direction, the associated Legendre polynomials possess ℓ−|m| zeros, whereas for the longitudinal direction, the trigonometric sin and cos functions possess 2|m| zeros.

When the spherical harmonic order m is zero (upper-left in the figure), the spherical harmonic functions do not depend upon longitude, and are referred to as zonal. Such spherical harmonics are a special case of zonal spherical functions. When ℓ = |m| (bottom-right in the figure), there are no zero crossings in latitude, and the functions are referred to as sectoral. For the other cases, the functions checker the sphere, and they are referred to as tesseral.

More general spherical harmonics of degree ℓ are not necessarily those of the Laplace basis  , and their nodal sets can be of a fairly general kind.[10]

, and their nodal sets can be of a fairly general kind.[10]

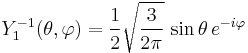

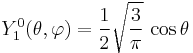

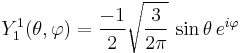

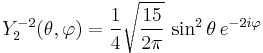

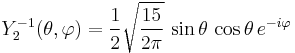

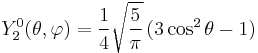

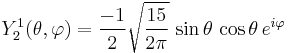

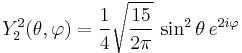

List of spherical harmonics

Analytic expressions for the first few orthonormalized Laplace spherical harmonics that use the Condon-Shortley phase convention:

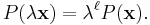

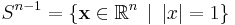

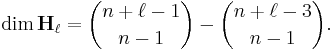

Higher dimensions

The classical spherical harmonics are defined as functions on the unit sphere S2 inside three-dimensional Euclidean space. Spherical harmonics can be generalized to higher dimensional Euclidean space Rn as follows.[11] Let Pℓ denote the space of homogeneous polynomials of degree ℓ in n variables. That is, a polynomial P is in Pℓ provided that

Let Aℓ denote the subspace of Pℓ consisting of all harmonic polynomials; these are the solid spherical harmonics. Let Hℓ denote the space of functions on the unit

obtained by restriction from Aℓ.

The following properties hold:

- The spaces Hℓ are dense in the set of continuous functions on Sn−1 with respect to the uniform topology, by the Stone-Weierstrass theorem. As a result, they are also dense in the space L2(Sn−1) of square-integrable functions on the sphere.

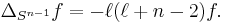

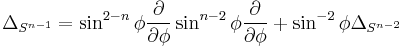

- For all ƒ ∈ Hℓ, one has

-

- where ΔSn−1 is the Laplace-Beltrami operator on Sn−1. This operator is the analog of the angular part of the Laplacian in three dimensions; to wit, the Laplacian in n dimensions decomposes as

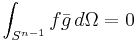

- It follows from the Stokes theorem and the preceding property that the spaces Hℓ are orthogonal with respect to the inner product from L2(Sn−1). That is to say,

-

- for ƒ ∈ Hℓ and g ∈ Hk for k ≠ ℓ.

- Conversely, the spaces Hℓ are precisely the eigenspaces of ΔSn−1. In particular, an application of the spectral theorem to the Riesz potential

gives another proof that the spaces Hℓ are pairwise orthogonal and complete in L2(Sn−1).

gives another proof that the spaces Hℓ are pairwise orthogonal and complete in L2(Sn−1).

- Every homogeneous polynomial P ∈ Pℓ can be uniquely written in the form

-

- where Pj ∈ Aj. In particular,

An orthogonal basis of spherical harmonics in higher dimensions can be constructed inductively by the method of separation of variables, by solving the Sturm-Liouville problem for the spherical Laplacian

where φ is the axial coordinate in a spherical coordinate system on Sn−1.

Connection with representation theory

The space Hℓ of spherical harmonics of degree ℓ is a representation of the symmetry group of rotations around a point (SO(3)) and its double-cover SU(2). Indeed, rotations act on the two-dimensional sphere, and thus also on Hℓ by function composition

for ψ a spherical harmonic and ρ a rotation. The representation Hℓ is an irreducible representation of SO(3).

The elements of Hℓ arise as the restrictions to the sphere of elements of Aℓ: harmonic polynomials homogeneous of degree ℓ on three-dimensional Euclidean space R3. By polarization of ψ ∈ Aℓ, there are coefficients  symmetric on the indices, uniquely determined by the requirement

symmetric on the indices, uniquely determined by the requirement

The condition that ψ be harmonic is equivalent to the assertion that the tensor  must be trace free on every pair of indices. Thus as an irreducible representation of SO(3), Hℓ is isomorphic to the space of traceless symmetric tensors of degree ℓ.

must be trace free on every pair of indices. Thus as an irreducible representation of SO(3), Hℓ is isomorphic to the space of traceless symmetric tensors of degree ℓ.

More generally, the analogous statements hold in higher dimensions: the space Hℓ of spherical harmonics on the n-sphere is the irreducible representation of SO(n+1) corresponding to the traceless symmetric ℓ-tensors. However, whereas every irreducible tensor representation of SO(2) and SO(3) is of this kind, the special orthogonal groups in higher dimensions have additional irreducible representations that do not arise in this manner.

The special orthogonal groups have additional spin representations that are not tensor representations, and are typically not spherical harmonics. An exception are the spin representation of SO(3): strictly speaking these are representations of the double cover SU(2) of SO(3). In turn, SU(2) is identified with the group of unit quaternions, and so coincides with the 3-sphere. The spaces of spherical harmonics on the 3-sphere are certain spin representations of SO(3), with respect to the action by quaternionic multiplication.

Generalizations

The angle-preserving symmetries of the two-sphere are described by the group of Möbius transformations PSL(2,C). With respect to this group, the sphere is equivalent to the usual Riemann sphere. The group PSL(2,C) is isomorphic to the (proper) Lorentz group, and its action on the two-sphere agrees with the action of the Lorentz group on the celestial sphere in Minkowski space. The analog of the spherical harmonics for the Lorentz group is given by the hypergeometric series; furthermore, the spherical harmonics can be re-expressed in terms of the hypergeometric series, as SO(3) = PSU(2) is a subgroup of PSL(2,C).

More generally, hypergeometric series can be generalized to describe the symmetries of any symmetric space; in particular, hypergeometric series can be developed for any Lie group.[12][13][14][15]

See also

- Spin-weighted spherical harmonics

- Sturm–Liouville theory

- Vector spherical harmonics

- Table of spherical harmonics

Notes

- ↑ A historical account of various approaches to spherical harmonics in three-dimensions can be found in Chapter IV of MacRobert 1967. The term "Laplace spherical harmonics" is in common use; see Courant & Hilbert 1962 and Meijer & Bauer 2004.

- ↑ The approach to spherical harmonics taken here is found in (Courant & Hilbert 1966, §V.8, §VII.5).

- ↑ Physical applications often take the solution that vanishes at infinity, making A = 0. This does not affect the angular portion of the spherical harmonics.

- ↑ Edmonds 1957, §2.5

- ↑ Watson & Whittaker 1927, p. 392.

- ↑ This is valid for any orthonormal basis of spherical harmonics of degree ℓ. For unit power harmonics it is necessary to remove the factor of

.

. - ↑ Watson & Whittaker 1927, p. 395

- ↑ Unsöld 1927

- ↑ Stein & Weiss 1971, §IV.2

- ↑ Eremenko, Jakobson & Nadirashvili 2007

- ↑ Solomentsev 2001; Stein & Weiss 1971, §Iv.2

- ↑ N. Vilenkin, Special Functions and the Theory of Group Representations, Am. Math. Soc. Transl., vol. 22, (1968).

- ↑ J. D. Talman, Special Functions, A Group Theoretic Approach, (based on lectures by E.P. Wigner), W. A. Benjamin, New York (1968).

- ↑ W. Miller, Symmetry and Separation of Variables, Addison-Wesley, Reading (1977).

- ↑ A. Wawrzyńczyk, Group Representations and Special Functions, Polish Scientific Publishers. Warszawa (1984).

References

- Cited references

- Courant, Richard; Hilbert, David (1962), Methods of Mathematical Physics, Volume I, Wiley-Interscience.

- Edmonds, A.R. (1957), Angular Momentum in Quantum Mechanics, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-07912-9.

- Eremenko, Alexandre; Jakobson, Dmitry; Nadirashvili, Nikolai (2007), "On nodal sets and nodal domains on

and

and  ", Université de Grenoble. Annales de l'Institut Fourier 57 (7): 2345–2360, MR2394544, ISSN 0373-0956

", Université de Grenoble. Annales de l'Institut Fourier 57 (7): 2345–2360, MR2394544, ISSN 0373-0956 - MacRobert, T.M. (1967), Spherical harmonics: An elementary treatise on harmonic functions, with applications, Pergamon Press.

- Meijer, Paul Herman Ernst; Bauer, Edmond (2004), Group theory: The application to quantum mechanics, Dover, ISBN 9780486437989.

- Solomentsev, E.D. (2001), "Spherical harmonics", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://eom.springer.de/S/s086690.htm.

- Stein, Elias; Weiss, Guido (1971), Introduction to Fourier Analysis on Euclidean Spaces, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08078-9.

- Unsöld, Albrecht (1927), "Beiträge zur Quantenmechanik der Atome", Annalen der Physik 387 (3): 355–393, doi:10.1002/andp.19273870304.

- Watson, G. N.; Whittaker, E. T. (1927), A Course of Modern Analysis, Cambridge University Press.

- General references

- E.W. Hobson, The Theory of Spherical and Ellipsoidal Harmonics, (1955) Chelsea Pub. Co., ISBN 978-0828401043.

- C. Müller, Spherical Harmonics, (1966) Springer, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Vol. 17, ISBN 978-3-540-03600-5.

- E. U. Condon and G. H. Shortley, The Theory of Atomic Spectra, (1970) Cambridge at the University Press, ISBN 0-521-09209-4, See chapter 3.

- J.D. Jackson, Classical Electrodynamics, ISBN 0-471-30932-X

- Albert Messiah, Quantum Mechanics, volume II. (2000) Dover. ISBN 0-486-40924-4.

- D. A. Varshalovich, A. N. Moskalev, V. K. Khersonskii Quantum Theory of Angular Momentum,(1988) World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, ISBN 9971-5-0107-4

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Spherical harmonics" from MathWorld.

External links

- Interactive calculator of spherical harmonics on Tal Carmon's Research Homepage

- Spherical harmonics applied to Acoustic Field analysis on Trinnov Audio's research page

- Spherical Harmonics by Stephen Wolfram and Nodal Domains of Spherical Harmonics by Michael Trott, the Wolfram Demonstrations Project

- An accessible introduction to spherical harmonics (by J. B. Calvert)

- Citizendium:Spherical harmonics

- OpenGL Spherical harmonics demo

- Allen McNamara's spherical harmonics animations

- Thorsten Becker's spherical harmonics animations

Software

- Spherical harmonics generator in OpenGL

- SHTOOLS: Fortran 95 software archive

- HEALPIX: Fortran 90 and C++ software archive

- SpherePack: Fortran 77 software archive

- SpharmonicKit: C software archive

- Frederik J Simons: Matlab software archive

- NFFT: C subroutine library (fast spherical Fourier transform for arbitrary nodes)

- Shansyn: spherical harmonics package for GMT/netcdf grd files

- SHAPE: Spherical HArmonic Parameterization Explorer

![\lambda\sin ^2(\theta) + \frac{\sin(\theta)}{\Theta(\theta)} \frac{d}{d\theta} \left [ \sin(\theta) \frac{d\Theta}{d\theta} \right ] = m^2](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/40ad0062202d673b235090ba6b2f5dc6.png)

![[L_z,L_+] = L_+,\quad [L_z,L_-] = -L_-, \quad [L_+,L_-] = 2L_z.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/558274c5fc6b184b8fc9376599bda2c2.png)